When you pick up a prescription at the pharmacy and see a cheaper version of a brand-name drug, you’re holding a product approved through the Abbreviated New Drug Application - or ANDA. It’s the reason generic drugs exist in the U.S. and why millions of people pay far less for their medications. But what exactly is an ANDA, and how does it work behind the scenes? This isn’t just regulatory jargon. It’s the engine that keeps generic drugs flowing, saving the U.S. healthcare system billions every year.

What Exactly Is an ANDA?

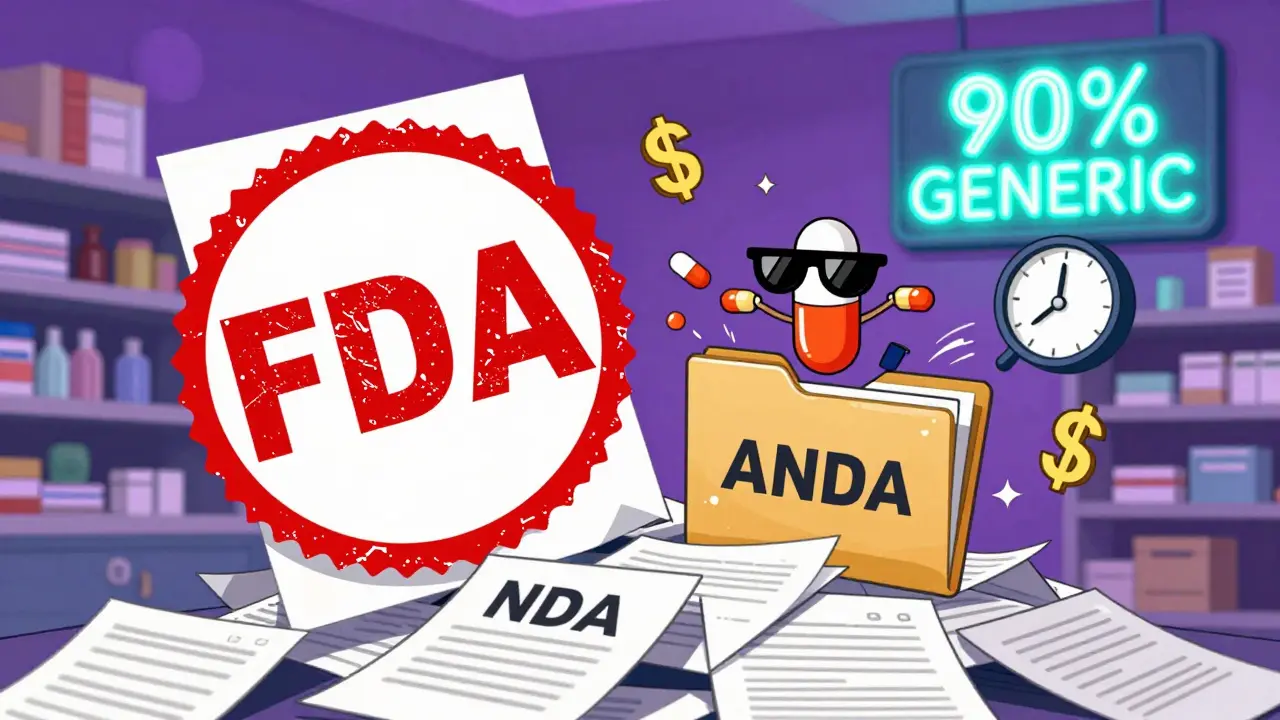

An ANDA is a formal request submitted to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to get approval to sell a generic version of a brand-name drug. Unlike the original drug maker, who had to prove the drug was safe and effective from scratch, a generic company using an ANDA doesn’t need to repeat those expensive clinical trials. Instead, they prove their version works the same way - using the same active ingredient, in the same strength, and delivered the same way - as the original. The ANDA pathway was created by the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984. Before that, generic drugs faced huge legal and scientific barriers. The law changed everything. It gave generic manufacturers a clear, faster, and cheaper path to market - as long as they met strict standards. Today, over 90% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S. are for generic drugs approved through ANDAs. That’s more than 3.5 billion prescriptions a year.How Does an ANDA Differ from an NDA?

The original drug maker files a New Drug Application, or NDA. That’s a massive undertaking. It can take 10 to 15 years and cost over $2.6 billion to get an NDA approved. The company has to run animal studies, multiple phases of human trials, and prove the drug works better than a placebo or existing treatments. An ANDA is completely different. It’s called “abbreviated” because it skips most of that. Instead of proving safety and efficacy from the ground up, the generic company points to the already-approved brand-name drug - called the Reference Listed Drug (RLD). The FDA has already confirmed the RLD is safe and effective. The generic company just needs to prove their version matches it exactly in key ways. Here’s the breakdown:- NDA: Full clinical data, new drug, high cost, long timeline

- ANDA: No new clinical trials, copy of existing drug, low cost, 3-4 years to approval

What Must an ANDA Prove?

It’s not enough to say your pill looks like the brand-name version. The FDA demands proof - hard data - that your generic drug is therapeutically equivalent. That means three things:- Pharmaceutical equivalence: Your drug has the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and route of administration (like oral tablet or injection) as the brand-name drug.

- Bioequivalence: Your drug gets into the bloodstream at the same rate and to the same level as the brand-name drug. This is proven through bioequivalence studies - usually with 24 to 36 healthy volunteers who take both the generic and the brand-name version under controlled conditions. The FDA requires that the 90% confidence interval for the ratio of the two drugs’ absorption (measured by AUC and Cmax) falls between 80% and 125%. That’s a tight window.

- Manufacturing quality: The generic company must show their production process meets the same quality standards as the original. This includes how the drug is made, tested, stored, and packaged.

What Happens After Submission?

Once an ANDA is submitted, the FDA reviews it for completeness. If it’s missing key data, they issue a “refuse-to-receive” letter. That’s not a rejection - it’s a request to fix and resubmit. If the application passes this initial check, it moves into full review. The FDA looks at everything: the chemistry, the manufacturing site, the bioequivalence data, the labeling. They inspect the manufacturing facility - often without warning. If the plant doesn’t meet current Good Manufacturing Practices (cGMP), the application is delayed or denied. If everything checks out, the FDA approves the ANDA and assigns it a six-digit number - like ANDA 214455 for the generic version of Eliquis. The generic drug can then be sold. But there’s one more hurdle: patents.The Hatch-Waxman Act and Patent Challenges

The Hatch-Waxman Act didn’t just create the ANDA pathway - it also created a system to balance innovation and competition. Brand-name companies list their patents on the drug in the FDA’s Orange Book. When a generic company files an ANDA, they must certify how they’re dealing with those patents. There are four types of certifications:- Paragraph I: No patents listed

- Paragraph II: Patents have expired

- Paragraph III: Patents will expire on a certain date - the generic waits until then

- Paragraph IV: The patent is invalid or won’t be infringed - this triggers a lawsuit from the brand-name company

Who Uses ANDAs and Why?

The ANDA pathway is used almost exclusively by generic drug manufacturers. The top players are Teva, Viatris (formerly Mylan), Sandoz, and Amneal. Together, they control nearly half the U.S. generic market. But hundreds of smaller companies also file ANDAs - especially for niche or older drugs. Why do they do it? Because it works. Generic drugs cost 80-85% less than brand-name versions within a year of launch. In 2023, generic drugs saved the U.S. healthcare system $313 billion. That’s not a guess - it’s from the Association for Accessible Medicines. For patients, this means lower out-of-pocket costs. For insurers, it means lower premiums. For taxpayers, it means lower Medicaid and Medicare spending. The Congressional Budget Office projects generic drugs will save $1.7 trillion between 2024 and 2033.

Where the System Struggles

The ANDA system is incredibly successful - but not perfect. It was designed for simple, small-molecule pills. It doesn’t work as well for complex drugs like inhalers, topical creams, or injectables with tricky delivery systems. In 2022, the FDA admitted that 32% of complete response letters (the official rejection notices) cited manufacturing control issues. Another 27% were due to insufficient bioequivalence data. Smaller companies, especially those without in-house regulatory teams, often struggle. One survey found that 68% of generic manufacturers had trouble proving bioequivalence for complex products. And then there’s the supply chain. Over 80% of generic drug ingredients come from India and China. A single factory shutdown - whether from quality issues, natural disasters, or political tension - can cause nationwide shortages. Experts warn this over-reliance is a systemic risk.What’s Next for ANDAs?

The FDA is adapting. In 2022, they launched the Complex Generic Drug Product Development program to help companies navigate tricky products. The new GDUFA IV agreement, effective in 2023, aims to raise the first-cycle approval rate from 65% to 90% by 2027. That means fewer back-and-forths, faster approvals, and more generics on shelves sooner. Industry analysts predict complex generics - like generic versions of biologics or advanced inhalers - will make up 25% of the generic market by 2028, up from 15% today. The ANDA pathway is evolving to meet those challenges.Why This Matters to You

You might not think about ANDAs when you refill your prescription. But if you’ve ever saved $50 on a medication because you chose the generic, you’ve benefited from this system. It’s not just about cost. It’s about access. Without ANDAs, millions of people couldn’t afford their medications. Chronic conditions like diabetes, high blood pressure, and depression would become unmanageable for many. The ANDA system isn’t perfect. It’s complex, bureaucratic, and sometimes slow. But it’s also one of the most effective public health tools ever created. It lets innovation and competition coexist. It keeps prices low without sacrificing safety. And it ensures that when a patent expires, the market opens up - not to monopolies, but to choice.Is an ANDA the same as a generic drug?

No. An ANDA is the application submitted to the FDA to get approval to sell a generic drug. The generic drug is the actual product you get at the pharmacy. The ANDA is the paperwork that proves it’s safe and effective.

Can any company file an ANDA?

Technically, yes - but it’s not easy. You need deep expertise in pharmaceutical manufacturing, regulatory affairs, and bioequivalence testing. Most ANDA filers are established generic drug companies with dedicated regulatory teams. Smaller companies often partner with consultants or contract research organizations to navigate the process.

Are generic drugs as safe as brand-name drugs?

Yes. The FDA requires that generic drugs meet the same strict standards for quality, strength, purity, and stability as brand-name drugs. Studies show that 97% of generic drugs approved through ANDAs are therapeutically equivalent to their brand-name counterparts. Millions of patients use generics safely every day.

How long does it take to get an ANDA approved?

Under current FDA timelines, a standard ANDA takes about 10 months to review. But the full process - from formulation to submission - usually takes 3 to 4 years. Delays can happen due to incomplete data, manufacturing issues, or patent disputes.

What’s the difference between an ANDA and a biosimilar?

ANDAs are for small-molecule generic drugs - like pills or injections with simple chemical structures. Biosimilars are for complex biologic drugs - like proteins made from living cells. Biosimilars follow a different pathway under the BPCIA (Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act), and they require more testing because they can’t be exact copies.

Why do some generic drugs look different from the brand name?

U.S. law requires generic drugs to look different from brand-name versions to avoid confusion. That means different colors, shapes, or markings. But the active ingredient, strength, and how it works in your body must be identical. The differences are only in inactive ingredients like dyes or fillers - and they can’t affect safety or effectiveness.

Comments

Neil Ellis

January 22, 2026 AT 00:25Man, I never thought about how wild it is that we’re basically stealing the FDA’s work to make drugs cheaper. The ANDA system is like the ultimate hack of capitalism - innovation gets rewarded, then everyone else gets to ride the coattails and save lives. I love it. My grandma’s blood pressure med costs $4 now instead of $400. That’s not just policy, that’s justice in pill form.

Lauren Wall

January 22, 2026 AT 19:16Generic drugs aren’t ‘cheaper’ - they’re just not overpriced. The brand names are the scam.

Ryan Riesterer

January 24, 2026 AT 05:18The bioequivalence criteria - 80–125% CI for AUC and Cmax - are empirically validated and statistically robust. The FDA’s threshold ensures therapeutic interchangeability without compromising pharmacokinetic fidelity. Deviations outside this range trigger拒收 (refusal to receive). The system works because it’s grounded in rigorous pharmacometrics, not marketing.

Liberty C

January 25, 2026 AT 04:01Let’s be real - the FDA approves these things like they’re grading a high school essay. ‘Oh, your tablet is 92% bioequivalent? Cute. Here’s ANDA 214455.’ Meanwhile, the same company that made this ‘identical’ generic also sells a $2000 ‘premium’ version of the same drug in Canada. The whole system is a theater of compliance. People think generics are ‘safe’? They’re just cheaper. And if you’re lucky, they work. Most of the time, yes. But don’t be naive.

shivani acharya

January 26, 2026 AT 11:1080% of ingredients from China and India? LOL. You think this is about health? It’s about control. Who owns the API supply chain? Who controls the raw materials? Who shut down factories during COVID and caused insulin shortages? The same people who made billions selling brand-name drugs. The ANDA system is a trap. It lets you think you’re getting choice, but you’re just getting the same oligopoly with a new label. And don’t even get me started on the ‘Paragraph IV’ patent chess game - that’s just corporate warfare disguised as competition. Wake up. This isn’t healthcare. It’s a rigged game with pills.

Sarvesh CK

January 28, 2026 AT 05:22The ANDA framework is a fascinating example of how regulation can be engineered to serve both public good and market efficiency. It balances the incentive structure for innovation - allowing the original developer to recoup R&D costs through patent exclusivity - while simultaneously enabling competition through a streamlined approval pathway. This equilibrium is delicate, and its success lies in its precision: not too lenient, not too rigid. The real challenge now is extending this model to complex generics and biosimilars, where biological variability introduces new layers of scientific and regulatory complexity. The future of global access to medicine may well depend on whether we can replicate this balance beyond small molecules.

Hilary Miller

January 30, 2026 AT 04:16This is why I love America. We make the rules, then let everyone else use them to save lives.

Daphne Mallari - Tolentino

January 31, 2026 AT 09:12While the economic implications of the ANDA pathway are undeniably significant, one must not overlook the epistemological assumptions underpinning bioequivalence. The assumption that AUC and Cmax are sufficient proxies for therapeutic equivalence ignores inter-individual pharmacodynamic variability, drug-drug interactions, and long-term clinical outcomes. The FDA’s reliance on healthy volunteers in controlled settings does not reflect the polypharmacy realities of the geriatric or immunocompromised populations who rely most heavily on generics. This constitutes a latent epistemic gap in regulatory science.

Chiraghuddin Qureshi

February 1, 2026 AT 14:45So the system works? 🤝💊 That’s beautiful. More generics = more people alive = more happy. 🙌 Let’s keep it going. #GenericRevolution