Before 1983, fewer than 40 treatments existed for rare diseases in the U.S. Today, more than 1,000 have been approved. What changed? The orphan drug exclusivity system.

Why orphan drug exclusivity exists

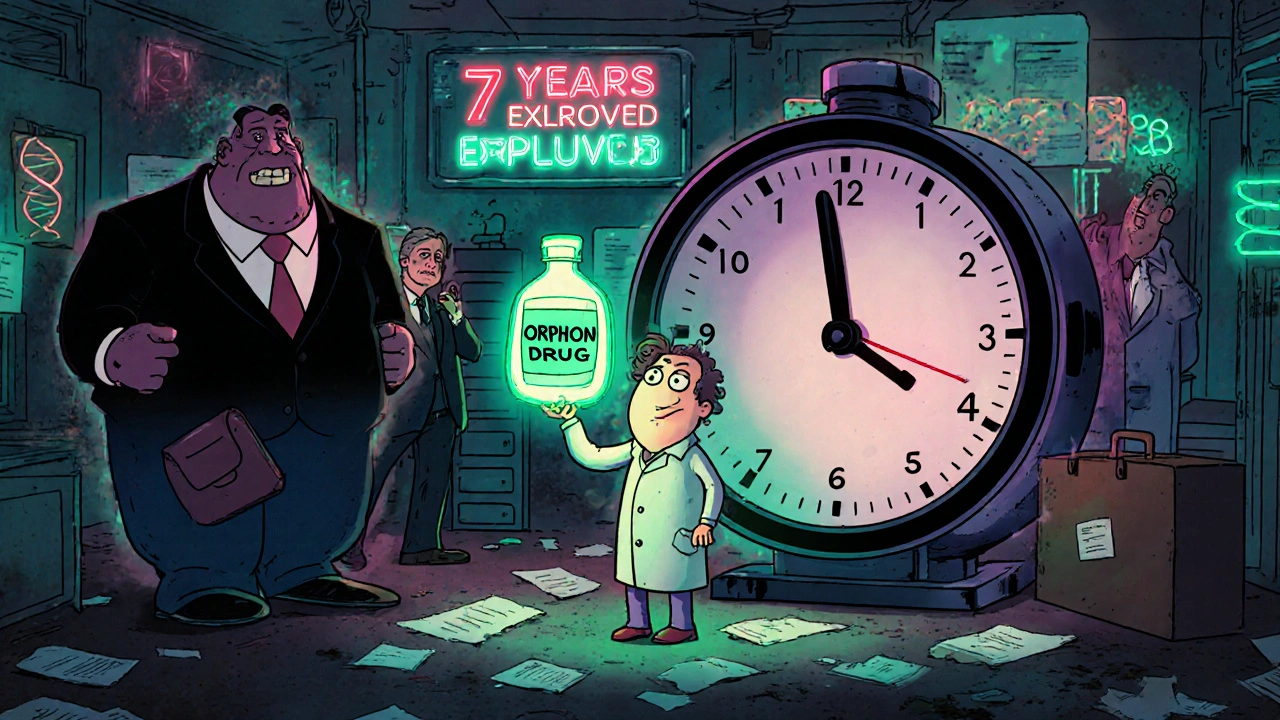

Developing a drug for a disease that affects only 5,000 people isn’t profitable. The costs of clinical trials, manufacturing, and regulatory review can hit $150 million or more. For most companies, that’s a losing bet. But for patients with rare diseases-conditions affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the U.S.-there were almost no treatment options. That’s why Congress passed the Orphan Drug Act in 1983. It didn’t just offer tax breaks or fee waivers. It gave something no other law offered: a guaranteed seven-year window where no competitor could sell the same drug for the same rare disease.This wasn’t charity. It was economics. The law created a clear, predictable path for companies to recover their investment. If you’re the first to get FDA approval for a drug to treat a rare condition, you get seven years of exclusive rights. No generics. No copies. Not even if another company develops the exact same molecule. That’s the core of orphan drug exclusivity.

How it actually works

Orphan drug exclusivity doesn’t start when a company applies. It doesn’t start when trials begin. It starts the day the FDA approves the drug for marketing. That’s when the seven-year clock ticks over.Here’s the catch: exclusivity is tied to the drug AND the disease. If a company gets approval for using Drug X to treat Disease Y, no one else can get approval for Drug X to treat Disease Y during those seven years. But if Drug X is later approved for a different disease-say, Disease Z-that’s fair game. Generics can come in for Disease Z, even while the original company still holds exclusivity for Disease Y.

That’s why companies sometimes chase multiple orphan designations for the same drug. A single molecule might get approved for three different rare conditions. Each one gets its own seven-year clock. This strategy, sometimes called “salami slicing,” has become common in the industry.

And here’s another twist: multiple companies can apply for orphan designation on the same drug-disease pair. But only the first to get FDA approval wins the exclusivity. It’s a race. The FDA doesn’t pick favorites. It doesn’t judge who’s better funded or who has the nicer lab. The first one to cross the finish line gets the prize.

Orphan exclusivity vs. patents

Most people assume patents are the main way drugs stay protected. They’re not, at least not for orphan drugs. In fact, IQVIA found that in 88% of cases, patent protection-not orphan exclusivity-was the primary barrier to generic entry.Why? Because patents protect the chemical structure or how the drug works. They can last 20 years from the date of filing. But patents can be challenged, invalidated, or expire early. Orphan exclusivity doesn’t care about patents. Even if a patent runs out, the FDA still can’t approve a copy of the drug for the same rare disease until the seven-year exclusivity period ends.

That’s a big deal. It means a company can file for orphan exclusivity even if their patent is weak or expired. The exclusivity stands on its own. It’s a safety net. For many small biotech firms, it’s the only reason they can get investors to fund a project.

What makes a drug qualify?

To get orphan designation, a drug must meet one of two criteria:- The disease affects fewer than 200,000 people in the U.S.

- Even if more than 200,000 people have it, the company can’t reasonably expect to make back its R&D costs from sales.

That second point is important. It means a drug for a disease affecting 150,000 people might not qualify if it’s likely to sell well. But a drug for a disease affecting 180,000 people could qualify if the treatment is too expensive to produce at scale.

Companies must submit data showing the disease prevalence-usually from medical literature, government health surveys, or hospital records. The FDA approves about 95% of properly filed applications. The real challenge isn’t getting the designation. It’s getting approval.

Limitations and controversies

Orphan exclusivity isn’t perfect. One major issue: some drugs get orphan status even when they’re already blockbuster products. Humira, for example, received multiple orphan designations for rare conditions even though it was already making billions treating common autoimmune diseases. Critics say this exploits the system.Another problem: the “clinical superiority” rule. If another company wants to get approval for the same drug for the same disease after exclusivity starts, they must prove their version is clinically superior. That means better effectiveness, fewer side effects, or easier dosing. The FDA has only accepted this argument in three cases since 1983. It’s nearly impossible to meet.

Then there’s pricing. Because there’s no competition for seven years, companies can set very high prices. A 2022 survey by the National Organization for Rare Disorders found that 42% of patient advocacy groups were concerned about how expensive orphan drugs had become. One drug for a rare muscle disorder costs over $300,000 a year. That’s not because of R&D-it’s because there’s no other option.

How it compares to Europe

The U.S. gives seven years. Europe gives ten. And Europe lets companies extend that to 12 years if they test the drug in children. The EU also has a way to shorten exclusivity from ten to six years if the drug is making too much money-something the U.S. doesn’t do.The EU is currently reviewing whether to lower the standard period to eight years for drugs that end up selling better than expected. The U.S. has no such plan. In fact, orphan designations in the U.S. have more than tripled since 2010-from 127 to 434 in 2022.

Who benefits the most?

The biggest winners? Small biotech firms. Without orphan exclusivity, most wouldn’t exist. The average cost to develop an orphan drug is $150 million. Only a handful of big pharma companies can afford that risk on their own. But small companies with one or two rare disease candidates? They rely on this system to attract funding, partner with larger firms, or get acquired.Patients benefit too. In 2022, orphan drugs accounted for 24.3% of all prescription drug sales in the U.S.-up from 16.1% in 2018. Oncology leads the way, with nearly half of all orphan drugs treating cancer. But there are also breakthroughs for rare neurological, metabolic, and blood disorders that barely existed 20 years ago.

What’s next?

By 2027, Deloitte predicts that 72% of all new drugs approved by the FDA will have orphan designation. That’s up from 51% in 2018. The trend isn’t slowing. Advances in genetic testing and personalized medicine mean we’re identifying more rare diseases every year-and more opportunities to treat them.But pressure is building. Lawmakers and insurers are asking: Is seven years too long? Should companies have to prove there’s still an unmet medical need? Should pricing be tied to the size of the patient population?

For now, the system stays. It’s not flawless. But it’s working. More than 6,500 orphan designations have been granted since 1983. Over 1,000 drugs have been approved. Millions of patients now have options where there were none before.

Orphan drug exclusivity isn’t about giving companies a free pass. It’s about making the impossible possible. Without it, most rare disease drugs would never be developed. With it, they’re becoming a standard part of modern medicine.

How long does orphan drug exclusivity last in the U.S.?

In the United States, orphan drug exclusivity lasts for seven years, starting from the date the FDA approves the drug for marketing. This period prevents other companies from getting approval for the same drug to treat the same rare disease, unless they can prove their version is clinically superior.

Does orphan exclusivity replace patents?

No, orphan exclusivity doesn’t replace patents. It works alongside them. Patents protect the chemical structure or method of use and can last up to 20 years. Orphan exclusivity protects the specific drug-disease combination and lasts seven years from FDA approval. In most cases, patents are the main barrier to generics, but orphan exclusivity provides an extra layer of protection even if patents expire.

Can multiple companies develop the same drug for a rare disease?

Yes, multiple companies can apply for orphan designation for the same drug and disease. But only the first one to get FDA approval wins the seven-year exclusivity. Others can still develop the drug, but they can’t get approval for that specific use until the exclusivity period ends-unless they prove their version is clinically superior, which has happened only three times since 1983.

What’s the difference between orphan designation and orphan approval?

Orphan designation is a status granted by the FDA when a drug is still in development and meets the criteria for treating a rare disease. It doesn’t guarantee approval. Orphan approval happens when the FDA approves the drug for marketing. Only after approval does the seven-year exclusivity period begin.

Why are some orphan drugs so expensive?

Orphan drugs are expensive because they’re developed for small patient populations, so companies must recoup high R&D costs from fewer sales. With no competition for seven years, manufacturers can set high prices. While this incentivizes development, it also leads to affordability concerns-42% of rare disease patient groups in a 2022 survey said pricing was a major issue.

Comments

Ryan Anderson

November 14, 2025 AT 01:14This system is honestly one of the few things in pharma that actually works 🙌

Without orphan exclusivity, we’d still be stuck with nothing for conditions like SMA or Duchenne MD. Companies wouldn’t touch them-too small a market, too much risk. But now? Kids are walking. People are living longer. It’s not perfect, but it’s a miracle compared to 1980.

Eleanora Keene

November 14, 2025 AT 17:59I just read this and I’m honestly in awe. The fact that a single molecule can get multiple orphan designations and each one gets its own 7-year window? That’s genius. Not shady-strategic. And honestly? If I were a biotech founder, I’d do the same thing. Patients need these drugs, and the system makes it possible.

Joe Goodrow

November 14, 2025 AT 23:57Let’s be real-this is corporate welfare with a pretty label. Humira getting orphan status for rare conditions while charging $70K a year? That’s not innovation, that’s exploitation. The FDA should have a cap on pricing when exclusivity kicks in. American patients are getting robbed.

Don Ablett

November 15, 2025 AT 13:46The distinction between orphan designation and orphan approval is critical and often misunderstood. Designation merely signals intent and eligibility under statutory criteria; approval constitutes regulatory validation of safety and efficacy. The seven-year exclusivity period commences only upon marketing authorization, and this temporal sequencing is fundamental to the integrity of the regulatory framework. One might argue that the system incentivizes efficient development, though the absence of cost-effectiveness thresholds remains problematic.

Kevin Wagner

November 16, 2025 AT 11:32Y’all act like this system is some kind of evil monopoly machine. Nah. This is what happens when you give small teams a fighting chance. Think about it-without this, 90% of these rare disease drugs wouldn’t exist. Companies with 12 people and a lab in a garage? They need this. The $300K drugs? Yeah, they’re expensive. But what’s the alternative? Letting kids die because Big Pharma won’t bother? I’ll take the high price over the empty pharmacy shelf any day.

gent wood

November 17, 2025 AT 06:57The comparison with Europe is particularly illuminating. The European model, with its potential for pediatric extension and dynamic exclusivity adjustments based on commercial performance, introduces a level of market responsiveness that the U.S. system conspicuously lacks. One might posit that the U.S. approach, while effective in stimulating development, risks entrenching unsustainable pricing structures due to its static nature.

Dilip Patel

November 19, 2025 AT 03:30USA always think they smartest but Europe do better. 10 years exclusivity and can reduce if make too much money? USA just let pharma rob people. Why no price control? Why no cap? India make generic for 1000$ and USA pay 300000$? This is not innovation this is robbery. America think money is god

Jane Johnson

November 20, 2025 AT 16:05It’s worth noting that the clinical superiority requirement is functionally meaningless. Only three approvals in forty years? That’s not a safeguard-it’s a rubber stamp for monopolies. The system was designed to encourage innovation, not to entrench price gouging under the guise of patient access.

Peter Aultman

November 21, 2025 AT 18:10Man I used to think this was all just corporate greed but reading this made me see it differently. Like yeah the prices are wild but if this system didn’t exist, we wouldn’t have half the treatments we do now. My cousin has a rare metabolic disorder and the drug she takes? Would’ve never been made 15 years ago. So… I’ll take the high cost over no hope.

Sean Hwang

November 23, 2025 AT 03:49Orphan drug = small group of people. High cost = make it back. Simple math. No competition = high price. That’s capitalism. But at least people get medicine. I’ve seen families cry because they found a drug that works. That’s worth something.

Barry Sanders

November 23, 2025 AT 13:52Salami slicing? More like corporate fraud. One drug, three orphan designations? That’s not innovation, that’s gaming the system. And the FDA lets it slide? Pathetic. This isn’t helping patients-it’s enriching executives.

Chris Ashley

November 25, 2025 AT 00:58So if I make a drug for a disease with 199k people and it turns out to be a blockbuster, I still get 7 years of monopoly? That’s insane. The 200k limit is a joke. They should audit this every year.

kshitij pandey

November 26, 2025 AT 14:52From India, I see this as a beautiful example of how policy can change lives. We don’t have this here, but I’m so glad it exists in the US. Even if prices are high, at least someone is trying. My uncle had a rare cancer-no treatment here. I wish we had this system.

Brittany C

November 26, 2025 AT 20:39It’s worth contextualizing that orphan exclusivity operates as a non-patent regulatory incentive, distinct from intellectual property protections. The convergence of market exclusivity and patent thickets creates a dual-layered barrier to generic entry, which, while beneficial for innovation, exacerbates pricing pressures in an already constrained market.

Sean Evans

November 26, 2025 AT 22:21And yet, here we are-paying $300K/year for a drug that costs $5K to make. 🤡 The FDA is complicit. The companies are greedy. And we’re the suckers who pay for it. This isn’t healthcare. It’s a Ponzi scheme with a lab coat.