Why Opioid Safety Matters More Than Ever

Every year, more than 108,000 people in the U.S. die from drug overdoses. In 2025, synthetic opioids like fentanyl were involved in 86% of those deaths. This isn’t just a crisis-it’s a daily reality for families, doctors, and patients trying to manage pain without losing their lives. The good news? We now have clear, science-backed ways to reduce those risks while still helping people feel better. The key is using opioids only when absolutely necessary-and knowing exactly how to use them safely when you do.

The New Rules for Prescribing Opioids

In February 2025, the CDC updated its guidelines for opioid prescribing, and these aren’t minor tweaks. They’re major shifts designed to stop harm before it starts. For acute pain-like after a dental procedure or a broken bone-the new standard is a three-day supply. That’s it. Seven-day prescriptions are only allowed if your doctor documents a clear medical reason. This change alone has cut new cases of long-term opioid use by up to 35% in practices that followed it closely.

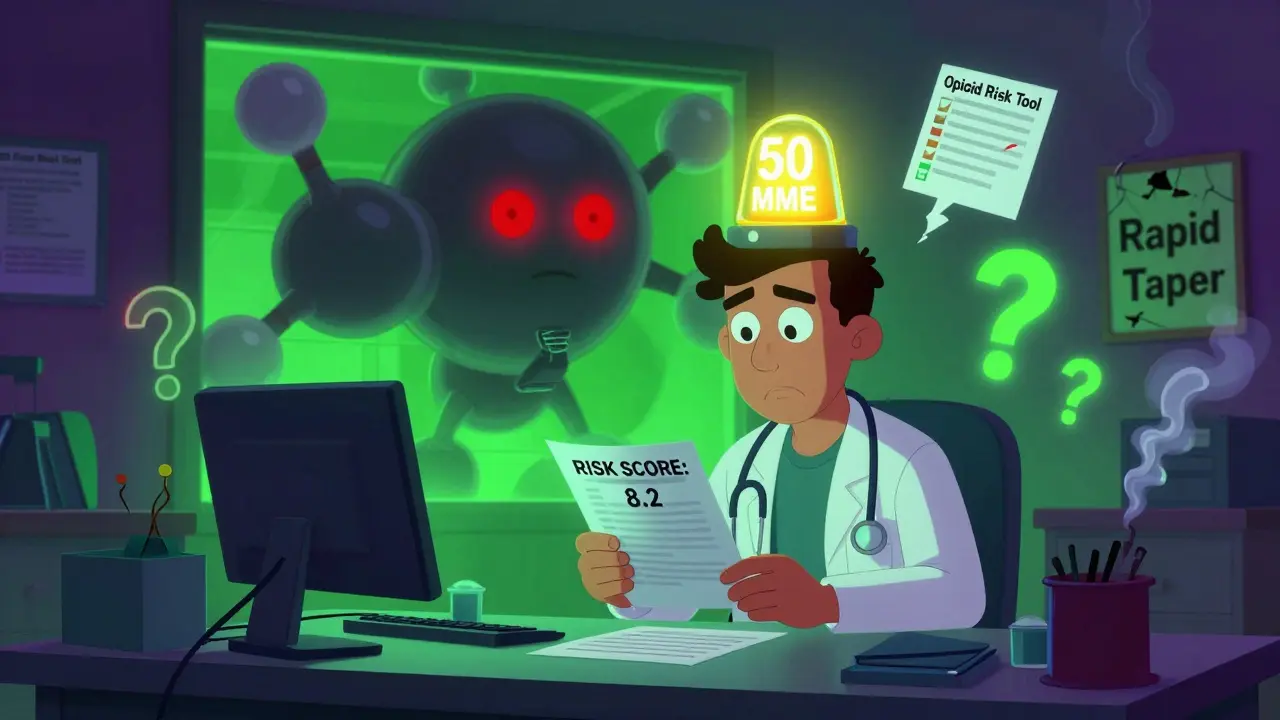

For chronic pain, the red flag is 50 morphine milligram equivalents (MME) per day. At that level, your risk of overdose jumps 2.8 times compared to lower doses. Doctors are now trained to pause and reevaluate every time a patient hits that mark. Doses above 90 MME per day should only be used in rare cases-like active cancer care or end-of-life treatment. Even then, the documentation requirements are strict. The FDA now requires all opioid labels to clearly state that 12.7% of patients on long-term therapy develop a moderate-to-severe opioid use disorder. That’s not a small number. It’s one in eight.

What You Need to Know About Risk Assessment

Not everyone who takes opioids is at the same risk. That’s why tools like the Opioid Risk Tool (ORT) and SOAPP are now part of standard care. These short questionnaires help doctors spot warning signs before they become problems. A score below 4 means low risk-standard monitoring applies. A score between 4 and 7 means moderate risk: more frequent check-ins, urine tests, and serious consideration of non-opioid options. A score above 8? That’s high risk. At this point, most experts agree opioids should be avoided unless an addiction specialist is involved.

Doctors are also required to check Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs (PDMPs) before writing a new opioid prescription. This simple step cuts overlapping prescriptions by 37%. It’s not perfect-adding 2.5 minutes per visit-but it saves lives. In states where PDMP use is mandatory, opioid-related ER visits have dropped significantly.

Alternatives to Opioids That Actually Work

Opioids aren’t the only way to manage pain-and they shouldn’t be the first. Multimodal pain management is now the gold standard. That means combining several safe, effective options:

- NSAIDs like ibuprofen or naproxen for inflammation and acute pain

- Acetaminophen for mild to moderate pain, especially when inflammation isn’t the issue

- Physical therapy for back pain, joint issues, and post-surgical recovery

- Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) to help retrain how the brain processes pain signals

- Topical treatments like lidocaine patches or capsaicin cream for localized pain

- CBD-based products, which are growing rapidly in use and evidence for chronic pain

Practices that offer these options side-by-side with medical care see opioid prescribing rates drop by 40-50%-without worsening pain outcomes. In fact, many patients report better long-term function because they’re not relying on a drug that dulls pain but doesn’t heal anything.

The Hidden Danger: Rapid Tapering

One of the biggest mistakes in recent years has been rushing to cut or stop opioids. In 2024, a major study found that patients whose opioids were abruptly discontinued had a 23% higher risk of suicide attempts. That’s not a coincidence. For people who’ve been on opioids for months or years, sudden withdrawal can trigger unbearable pain, anxiety, and despair. The FDA’s 2025 labeling update now explicitly warns against rapid tapering. The goal isn’t to eliminate opioids overnight-it’s to reduce them slowly, safely, and with support. If you’re on a high dose and want to cut back, work with your doctor on a plan that takes weeks or months-not days.

What Happens When Guidelines Don’t Fit Real Life

Not every patient fits neatly into a guideline. Surgeons, for example, argue that 15-20% of patients after major surgery genuinely need opioids longer than seven days. Veterans with PTSD and chronic pain often need more complex, coordinated care. The VA’s Opioid Safety Initiative (OSI) Toolkit helps with that-it ties together mental health, pain management, and substance use services in one system. Primary care doctors using the toolkit report better outcomes for complex cases.

But the system isn’t perfect. Smaller clinics still struggle with electronic health record updates needed to trigger safety alerts. Some patients report being cut off abruptly when their doctor fears legal liability. And there’s a nationwide shortage of 12,500 pain specialists, especially in rural areas. The challenge isn’t just about rules-it’s about resources. We need more therapists, more pain clinics, more training for frontline providers.

What Patients Can Do Right Now

You don’t have to wait for the system to fix itself. Here’s what you can do:

- Ask your doctor: "Is this opioid really necessary?" and "What are my alternatives?"

- Request a PDMP check before any new prescription is written.

- Keep your meds in a locked box. Never share them.

- Use naloxone if you’re on opioids-even if you think you don’t need it. It’s a lifesaver.

- Track your pain and mood. Use a simple journal or app. This helps your doctor adjust your plan.

- If you’ve been on opioids for more than three months, ask about a slow taper plan-even if you feel fine.

These steps aren’t about distrust. They’re about empowerment. You’re not just a patient-you’re a partner in your care.

The Bigger Picture: Where We’re Headed

By 2027, experts predict 65% of acute pain episodes will be managed without opioids. That’s up from 48% in 2025. The NIH is pouring $125 million into developing non-addictive pain treatments. Insurance companies are starting to cover more physical therapy and behavioral health services. States are tightening limits on how long opioids can be prescribed for acute pain-from three to seven days, depending on location.

But the real win isn’t in the numbers. It’s in the stories: the person who avoided addiction after a sports injury, the veteran who found relief through CBT instead of pills, the grandmother who managed arthritis pain with heat, movement, and topical creams. These aren’t exceptions. They’re the future.

The goal isn’t to eliminate opioids. It’s to use them wisely. To make sure they’re a tool-not a trap. And to make sure no one has to choose between pain and survival.

What is the maximum daily opioid dose considered safe?

According to the 2025 CDC guidelines, doses above 90 morphine milligram equivalents (MME) per day should be avoided except in rare cases like active cancer, palliative care, or end-of-life treatment. At 50 MME per day, overdose risk increases 2.8 times, so doctors are required to reassess benefits and risks at that level. Most patients do not need doses higher than 50 MME for long-term pain management.

Can I get opioids for a toothache or sprained ankle?

Yes, but only for a maximum of three days, unless your doctor documents a specific reason for a longer supply. For most dental procedures or minor injuries, non-opioid options like ibuprofen and acetaminophen are just as effective-and carry no risk of addiction. If your doctor prescribes more than three days, ask why and whether non-opioid alternatives were tried first.

Are opioids safe if I’ve been taking them for years?

Long-term opioid use carries increasing risks over time, including tolerance, dependence, and higher overdose risk-even if you’re not misusing them. The FDA now requires labels to state that 12.7% of long-term users develop opioid use disorder. If you’ve been on opioids for more than three months, talk to your doctor about whether a slow, supervised taper might improve your long-term health, even if you feel fine now.

What should I do if my doctor wants to stop my opioids suddenly?

You have the right to a safe, gradual taper plan. Sudden discontinuation increases risks of severe withdrawal, uncontrolled pain, and suicide. Ask for a written plan that reduces your dose slowly over weeks or months. If your doctor refuses, seek a second opinion from a pain specialist or addiction medicine provider. The FDA and CDC both warn against abrupt tapering.

Is naloxone really necessary if I’m not using opioids recreationally?

Yes. Even prescribed opioids can cause accidental overdose, especially if mixed with other medications like benzodiazepines or alcohol. Naloxone is a safe, easy-to-use nasal spray that reverses opioid overdoses. Many pharmacies now offer it without a prescription. If you’re on opioids, keep naloxone on hand. It’s not a sign of suspicion-it’s a sign of responsibility.

What are the best non-opioid options for chronic back pain?

Research shows the most effective combination for chronic back pain includes physical therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and regular movement like walking or swimming. NSAIDs (like naproxen) can help with flare-ups. Topical treatments such as lidocaine patches or capsaicin cream reduce localized pain without systemic side effects. Some patients also benefit from acupuncture or mindfulness-based stress reduction. These approaches don’t just reduce pain-they improve function and quality of life.

Final Thoughts: Safety Isn’t a Restriction-It’s a Standard

Medication safety isn’t about taking away options. It’s about making sure the right tools are used in the right way. Opioids have a place in pain care-but only when everything else has been tried, and only when the risks are fully understood. The data is clear: better guidelines, better alternatives, and better communication lead to fewer deaths, fewer addictions, and better lives. You don’t have to choose between pain and safety. With the right approach, you can have both.

Comments

Gran Badshah

December 28, 2025 AT 05:36Now I'm stuck between a rock and a hard place.

Ellen-Cathryn Nash

December 29, 2025 AT 23:30Three-day limit? Good. Maybe if people stopped treating opioids like a spa day, we wouldn't have 100k dead bodies a year. Your 'abandonment' is the cost of being responsible.

Samantha Hobbs

December 30, 2025 AT 19:39It's not about being mean-it's about being smart. Slow tapers + CBT + physical therapy saved her. She's walking again without pills. I wish more people knew this wasn't a punishment, it was a second chance.

Nicole Beasley

January 1, 2026 AT 16:50And yes, I’m crying typing this. 😭

sonam gupta

January 3, 2026 AT 03:23Julius Hader

January 3, 2026 AT 22:11It wasn't his fault. It was the system. That's why I support the new rules. Not because I'm angry. Because I'm grieving. And I don't want another family to feel this.

James Hilton

January 4, 2026 AT 00:50Meanwhile, my dentist gave me 60 pills for a wisdom tooth removal. I gave 50 to my cousin who 'needed it more'.

Oh wait-this is America. We don't do science. We do memes and moral panic.

Mimi Bos

January 4, 2026 AT 10:31also i typoed like 5 times in this comment lol

Payton Daily

January 6, 2026 AT 02:44When you numb the body, you numb the soul.

Maybe the real crisis isn't opioids. It's that we've forgotten how to endure. How to sit with discomfort. How to be human without a pill to fix it.

The system isn't broken. We are.

Kelsey Youmans

January 7, 2026 AT 10:50Policy without infrastructure is performative.

Debra Cagwin

January 8, 2026 AT 05:21And if you're on opioids and you're worried-get naloxone. It's free at most pharmacies. It's not a failure. It's a safety net.

You deserve to be safe. You deserve to be heard. And you are not your prescription.