When a brand-name drug’s patent expires, patients and insurers expect cheaper generic versions to hit the market. But in reality, that’s not always what happens. Instead, a legal maze of patent lawsuits, settlement deals, and questionable patent listings often delays generics for years - even after the original patent runs out. This isn’t just a legal issue. It’s a public health issue. Every month a generic is held back, Americans pay billions more for medicines they could be getting at a fraction of the cost.

How the System Was Supposed to Work

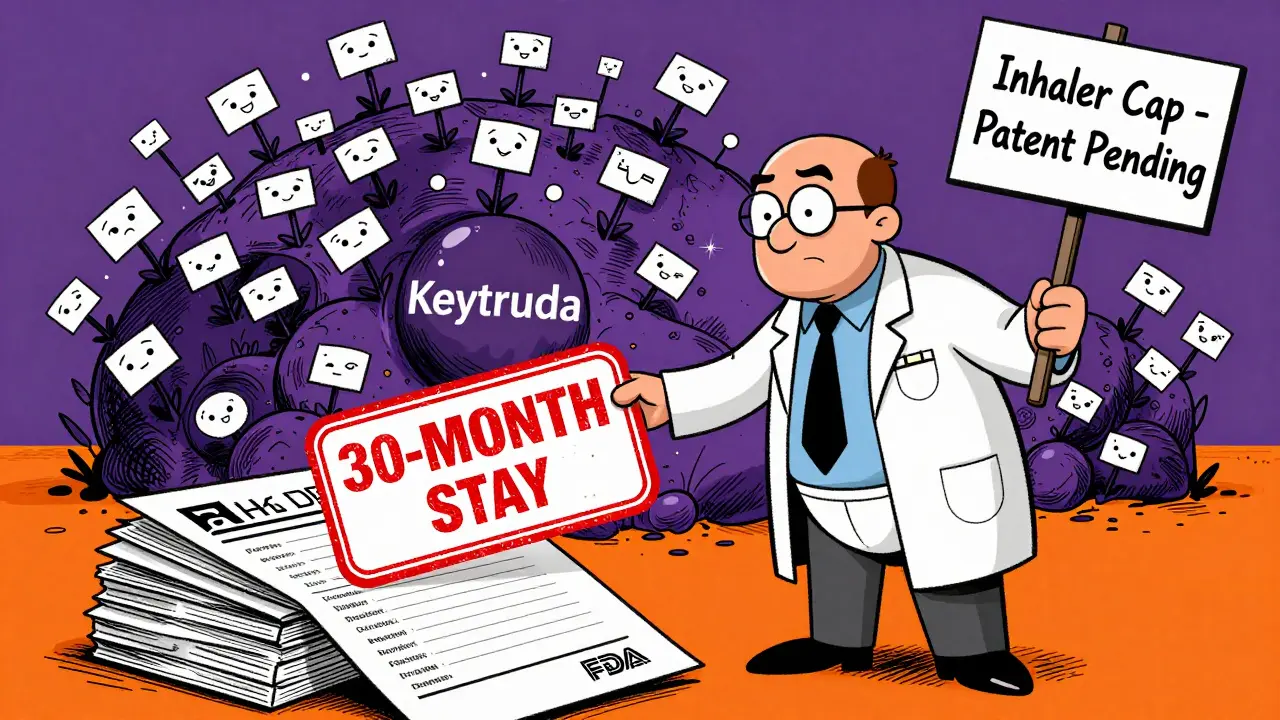

The Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984 was designed to balance two goals: reward innovation and speed up access to affordable drugs. It gave brand-name companies a limited window of exclusivity - usually 20 years from patent filing - while creating a clear path for generics to enter the market. Generic manufacturers file what’s called an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA). If they believe a brand’s patent is invalid or won’t be infringed, they file a Paragraph IV certification. That’s the trigger. Once that’s filed, the brand company has 45 days to sue. If they do, the FDA can’t approve the generic for up to 30 months, no matter how strong the case.This 30-month stay was meant to give courts time to sort out real disputes. But over time, it became a tool for delay. Instead of protecting genuine innovation, it’s often used to block competition through legal tactics that have little to do with the actual drug.

The Orange Book: A Legal Tool Turned Weapon

The FDA’s Orange Book lists patents tied to brand-name drugs. Only certain patents belong there - those covering the active ingredient, how it’s made, how it’s used, or the formulation. But companies have found loopholes. They list patents for things like inhaler caps, dose counters, packaging, or even manufacturing equipment. These have nothing to do with the drug’s effectiveness, but they still trigger the 30-month stay.In 2025, a landmark case between Teva and Amneal over the asthma inhaler ProAir® HFA changed that. Judge Chesler ruled that patents on the inhaler’s dose counter didn’t qualify for Orange Book listing because they didn’t claim “the drug for which the application was approved.” The drug was albuterol sulfate - not the plastic part you hold. That ruling is now being used to challenge hundreds of similar patents. Skadden’s analysis estimates 15-20% of all Orange Book listings could be invalid under this standard.

Meanwhile, the FDA is moving to require brand companies to certify under penalty of perjury that every patent they list meets the legal standard. That change, expected in mid-2026, could wipe out thousands of questionable listings overnight.

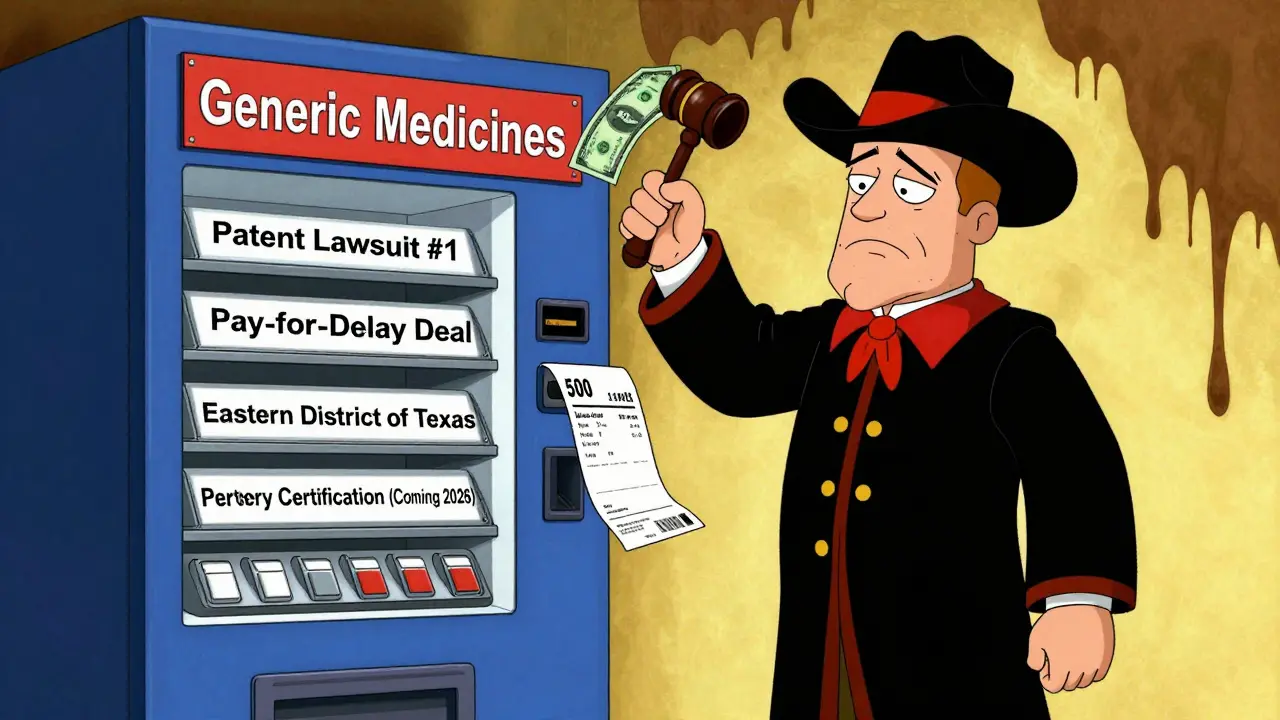

Serial Litigation: The Patent Thicket Strategy

Brand companies don’t just file one patent. They file dozens - sometimes over a hundred - on a single drug. Oncology drugs like Keytruda and Opdivo have more than 200 patents each. The average small molecule drug now has 78 patents, up from 37 just a decade ago. This is called a “patent thicket.”Here’s how it works: When one patent expires or gets invalidated, the brand company sues again using a different patent - often one they held back, waiting for the right moment. This creates a chain of lawsuits. One case ends, another begins. The generic manufacturer spends millions defending itself. The FDA sits idle. Patients wait.

According to the Association for Accessible Medicines (AAM), some drugs have seen generic entry delayed by 7 to 10 years after the original patent expired. Eliquis, a blood thinner, has 67 patents protecting it. Semaglutide (Ozempic, Wegovy) has 152. These aren’t breakthroughs - they’re tweaks. But they’re enough to keep generics off shelves.

Settlements: Are They Helping or Hurting?

When a brand company sues a generic, they can settle. Sometimes, the generic agrees to delay its market entry in exchange for cash or other benefits. These are called “pay-for-delay” deals - and the FTC has spent years trying to stop them.But here’s the twist: a June 2025 report from the IQVIA Institute, commissioned by AAM, found that patent settlements actually sped up generic entry by more than five years on average. Why? Because without the option to settle, many generic companies simply don’t file Paragraph IV challenges at all. They can’t afford the risk. So instead of one delayed entry, you get zero.

That’s the real problem. The FTC sees pay-for-delay as anti-competitive. But the industry sees it as a necessary compromise. If you remove settlements, you don’t get more generics - you get fewer filings. And that means fewer patients get access.

Where the Lawsuits Are Happening

Not all courts are the same. The Eastern District of Texas has become the go-to venue for pharmaceutical patent cases. In 2024, 38% of all patent lawsuits were filed there - more than double the number in Delaware or California. Why? Because judges there are experienced in patent law, procedures favor plaintiffs, and juries tend to side with patent holders.That’s made it a magnet for brand companies. It’s also drawn criticism for “forum shopping” - picking the court most likely to rule in your favor. But despite calls to limit venue choice, the trend continues. The Federal Circuit has upheld the practice, and with no major reform in sight, the Eastern District of Texas remains the epicenter of pharmaceutical litigation.

The Financial Cost

This isn’t just about legal strategy. It’s about money. The FTC estimates that improper patent listings delay generic entry for about 1,000 drugs every year. That costs the U.S. healthcare system $13.9 billion annually. Patients pay more. Insurers pay more. Medicare and Medicaid pay more.And the delays are getting longer. In 2005, the average time from brand drug approval to first generic entry was 14 months. By 2024, it had doubled to 28 months. For cancer drugs, it’s worse - an average of 5.7 years after patent expiry before a generic even appears.

Meanwhile, law firms like Fish & Richardson and Quinn Emanuel are seeing 35-40% annual revenue growth in their patent litigation practices. The system is working - just not for patients.

What’s Changing Now?

There are signs the tide may be turning. The FTC issued over 300 warnings in 2024 against improper Orange Book listings. In May 2025, they sent 200 more, targeting major companies like Teva and Amgen. The Department of Justice held listening sessions with generic manufacturers in March 2025, documenting how device patents are being misused.Generic companies are also fighting back with inter partes review (IPR) - a faster, cheaper way to challenge patents at the Patent Trial and Appeal Board. IPR filings against pharma patents jumped 47% from 2023 to 2024. But the Supreme Court’s April 2025 ruling in Smith & Nephew v. Arthrex made it harder for some generics to qualify for IPR, adding another layer of complexity.

The real game-changer may be the FDA’s new certification rule. If brand companies must swear under penalty of perjury that their patents meet the legal standard, many won’t risk it. That could clear the path for hundreds of generics to enter the market within months.

What’s Next?

The number of pharmaceutical patent lawsuits is expected to grow 25-30% per year through 2027, according to Lex Machina. Biosimilars - cheaper versions of complex biologic drugs - are entering the mix, and they come with even more patents. A single biologic can have over 100 patents. That means more lawsuits, more delays, and more money spent on legal fees instead of medicine.For now, the system is broken. The Hatch-Waxman Act was meant to bring down drug prices. Instead, it’s become a legal shield for price gouging. The tools to fix it exist - tighter Orange Book rules, fewer serial lawsuits, better IPR access. But without political will, patients will keep paying the price.

Why do generic drugs take so long to come out after a patent expires?

Even after a patent expires, brand companies often file new lawsuits using other patents - sometimes on packaging or delivery devices - to trigger a 30-month FDA approval delay. These tactics, called serial litigation, can push generic entry back by years. Some drugs face over a dozen lawsuits before a generic finally gets approved.

What is the Orange Book, and why does it matter?

The Orange Book is the FDA’s official list of patents linked to brand-name drugs. Only patents covering the drug’s active ingredient, formulation, use, or manufacturing can be listed. But many companies list irrelevant patents - like those for inhaler caps - to block generics. A 2025 court ruling clarified that such patents don’t qualify, which could invalidate thousands of listings.

Are pay-for-delay settlements really bad for patients?

The FTC says yes - they delay generics and inflate prices. But industry data shows settlements often lead to earlier generic entry than if no deal is made. Without the option to settle, many generic companies won’t risk filing a patent challenge at all. So while some settlements are abusive, banning them entirely could reduce overall generic access.

Why is the Eastern District of Texas so important in these lawsuits?

It’s become the most popular court for patent cases because judges there are experienced, procedures favor patent holders, and juries tend to award high damages. In 2024, 38% of all pharma patent lawsuits were filed there - more than double the next highest court. Critics call it forum shopping; the industry calls it efficiency.

Can generic companies challenge patents without going to court?

Yes. They can file an inter partes review (IPR) at the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB), which is faster and cheaper than federal court. IPR filings against pharma patents rose 47% in 2024. But a 2025 Supreme Court ruling made it harder for some generics to qualify, limiting who can file these challenges.

What’s the biggest threat to affordable generics today?

The biggest threat is the abuse of the patent system - listing weak or irrelevant patents to trigger legal delays. With over 1,000 drugs affected annually and costs exceeding $13 billion per year, this isn’t about innovation. It’s about extending monopolies. The FDA’s new certification rule in 2026 could be the most effective tool yet to stop it.

Comments

Shweta Deshpande

January 27, 2026 AT 14:57Honestly, I’ve seen this play out with my dad’s diabetes meds - took 5 years after patent expiry for a cheap generic to show up. He was buying half-pills just to stretch the brand-name ones. It’s not just corporate greed, it’s a whole system rigged to keep people sick and paying. I’m glad someone’s finally calling it out.

Karen Droege

January 28, 2026 AT 22:13Let’s be real - this isn’t innovation, it’s legal extortion. Patents on inhaler caps?! That’s like patenting the handle of a hammer because you used it to build the house. The FDA’s new perjury rule is the first real shot in the arm this system’s had in decades. If they actually enforce it, we could see 300+ generics hit the market next year. Imagine that.

Neil Thorogood

January 29, 2026 AT 05:24Law firms making 40% annual growth while people skip insulin doses? 😂

Ashley Karanja

January 29, 2026 AT 11:50The structural irony here is that Hatch-Waxman was designed as a compromise - innovation incentivized, access enabled - but the legal architecture has been weaponized by actors who understand the system better than the regulators do. The 30-month stay was never meant to be a litigation trigger; it was meant to be a pause button. Now it’s a full stop. And the Eastern District of Texas? That’s not a courthouse - it’s a patent casino where the house always wins. The real tragedy is that the players who need to win - patients - aren’t even allowed at the table.

Conor Flannelly

January 30, 2026 AT 11:48I’ve spent years in pharma compliance in Dublin, and I’ve seen the same games played here - even with EU generics. The Orange Book is a joke. I once reviewed a patent for a pill bottle’s screw thread. It was listed. It was challenged. It was upheld. The patient paid €400 a month for a drug that could’ve cost €12. This isn’t law. It’s performance art for shareholders.

And don’t get me started on pay-for-delay. Yes, some settlements speed things up - but only because the generics are too broke to fight. It’s like paying off a mugger so he doesn’t hit you *this* week. The real fix? Strip the 30-month stay of its automatic power. Let courts decide fast, or let generics in immediately. Let the market decide, not the lawyers.

Also - that 2025 Teva vs Amneal ruling? That’s the crack in the dam. Once judges start saying ‘nope, that’s not a drug patent,’ the whole house of cards starts shaking. And if the FDA starts demanding perjury certifications? Good. Let them sweat. I’ve seen too many affidavits signed with one hand while holding a Starbucks in the other.

Napoleon Huere

January 31, 2026 AT 04:19It’s wild how we celebrate innovation in tech - open source, rapid iteration, disruption - but in pharma, we treat every tiny tweak like a miracle. A new pill shape? Patent. A different color? Patent. A new cap? Patent. Meanwhile, the actual molecule? Expired. We’ve turned medicine into a legal puzzle instead of a public good. And the worst part? We let them get away with it because we’re too tired to fight.

Jessica Knuteson

February 1, 2026 AT 07:37Everyone says ‘patients pay more’ but no one asks who benefits from the lawsuits. Law firms. Patent trolls. Big Pharma execs with stock options. The real cost isn’t $13B - it’s the lives lost because someone couldn’t afford their meds for 3 extra years. That’s not a statistic. That’s murder by bureaucracy.

Marian Gilan

February 2, 2026 AT 00:52Big Pharma owns the FDA. The DOJ. The courts. The whole thing’s a front. You think that 2025 ruling was real? Nah. It’s a distraction. They’re letting us think we’re winning so we stop looking at the real puppet masters - the same people who run the Fed and the CIA. Mark my words: by 2027, they’ll patent the air you breathe if it helps them make another billion.

Robin Van Emous

February 2, 2026 AT 15:36I get why generics don’t always sue - it’s expensive, risky, and slow. But settlements? They’re not evil if they get drugs to people faster. I’m not saying abuse is okay - but banning settlements might mean no generics at all. That’s worse. Maybe the answer isn’t to punish the deals, but to fix the system so companies don’t feel forced into them. Less fear. More fairness.

rasna saha

February 3, 2026 AT 15:44My cousin in Mumbai can’t get her epilepsy meds because the Indian generic maker got sued by a U.S. company over a patent on a tablet coating. This isn’t just an American problem. It’s global. If we don’t fix this, the rich get medicine, the poor get paperwork.

Conor Murphy

February 5, 2026 AT 13:02My grandpa died because he couldn’t afford his heart med. He was 78. The patent expired in 2019. Generic came in 2024. He didn’t make it to 2020. This isn’t policy. It’s personal.

Patrick Merrell

February 7, 2026 AT 10:41They’re all corrupt. Every single one. Pharma, FDA, courts - it’s all one big money machine. And you think the ‘new rule’ will change anything? Please. They’ll just rewrite the patents as ‘delivery systems’ or ‘user experience enhancements.’ They always do. This system was designed to fail. And we’re just the ones paying for it.