Osteoarthritis Autoimmune Risk Calculator

Enter your details and click "Calculate Autoimmune Risk" to see the assessment.

When you hear the word osteoarthritis, you probably picture “wear and tear” on the knees or hips. But recent research shows the immune system can play an active role, turning a mechanical problem into an inflammatory one. This article breaks down what autoimmunity means for osteoarthritis, why it matters for patients, and what doctors are doing about it.

Key Takeaways

- Osteoarthritis isn’t just a mechanical disease; immune cells often drive joint damage.

- Autoimmune mechanisms involve specific genes (like HLA‑DRB1) and cytokines that sustain inflammation.

- Detectable biomarkers in blood or synovial fluid can signal an autoimmune component.

- Treatment is shifting toward drugs that modulate the immune response, not just pain relief.

- Ongoing trials aim to prove disease‑modifying osteoarthritis drugs (DMOADs) can halt or reverse joint loss.

What Is Osteoarthritis?

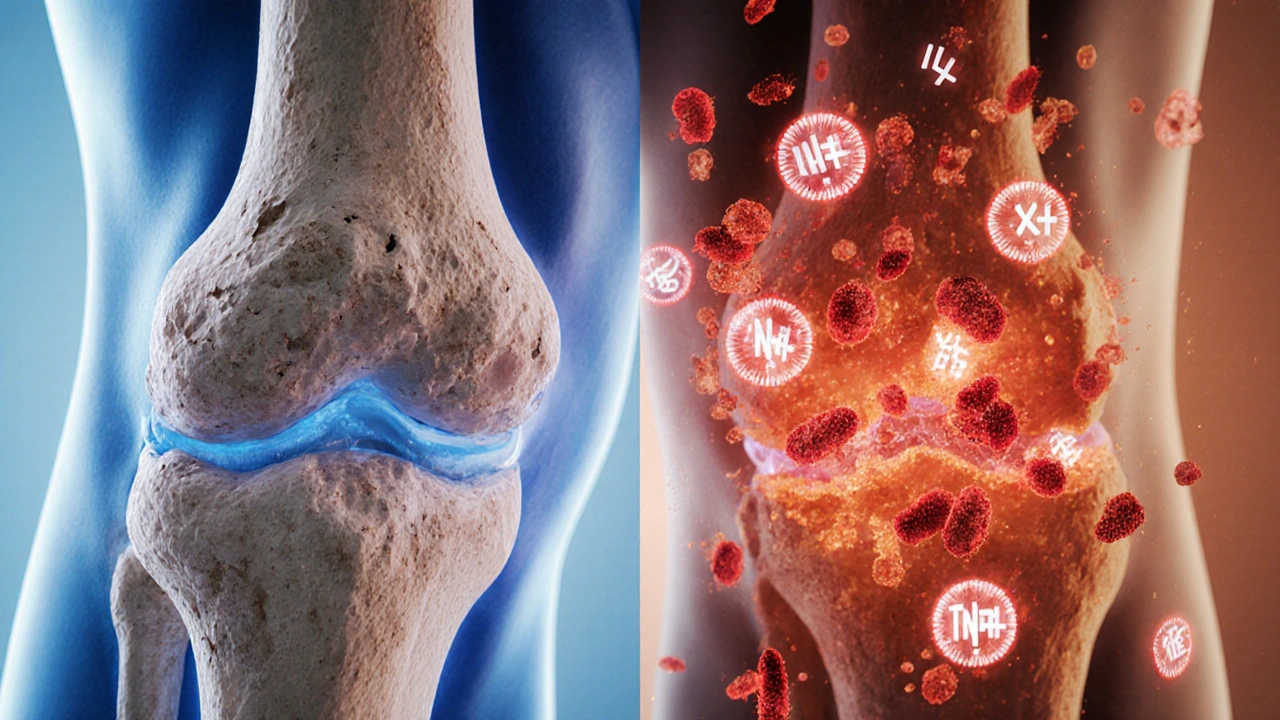

Osteoarthritis is a chronic joint disorder characterized by cartilage breakdown, bone remodeling, and synovial inflammation. It typically affects weight‑bearing joints such as the knees, hips, and spine.

Traditional thinking linked the disease to age, genetics, and mechanical overload. While those factors still matter, they don’t explain why some people develop severe joint damage with relatively low wear.

The Immune System’s Basic Playbook

Immune system is the body’s network of cells, tissues, and molecules that defend against infections and maintain tissue homeostasis. It's divided into innate (quick, non‑specific) and adaptive (slow, highly specific) branches.

When everything works right, immune cells clean up debris and promote repair. When the system goes haywire, it can attack the body’s own tissues-a phenomenon known as autoimmunity.

Autoimmunity: When Self Becomes Enemy

Autoimmunity is an immune response directed against the body’s own proteins, cells, or organs. Classic examples include rheumatoid arthritis and type1 diabetes.

In osteoarthritis, autoimmunity shows up as persistent synovial inflammation, even when mechanical stress is low. Certain genes and cytokine patterns tip the balance toward this chronic state.

Genetic Clues: The HLA‑DRB1 Connection

HLA‑DRB1 is a classII major histocompatibility complex gene that presents antigens to T‑cells. Specific alleles (e.g., *04:01) are linked to higher risk of autoimmune diseases.

Studies in 2023‑2024 found that individuals carrying the HLA‑DRB1*04:01 allele were 1.8times more likely to develop osteoarthritis with pronounced synovitis. The allele seems to facilitate presentation of cartilage‑derived peptides, nudging the adaptive immune system to recognize them as threats.

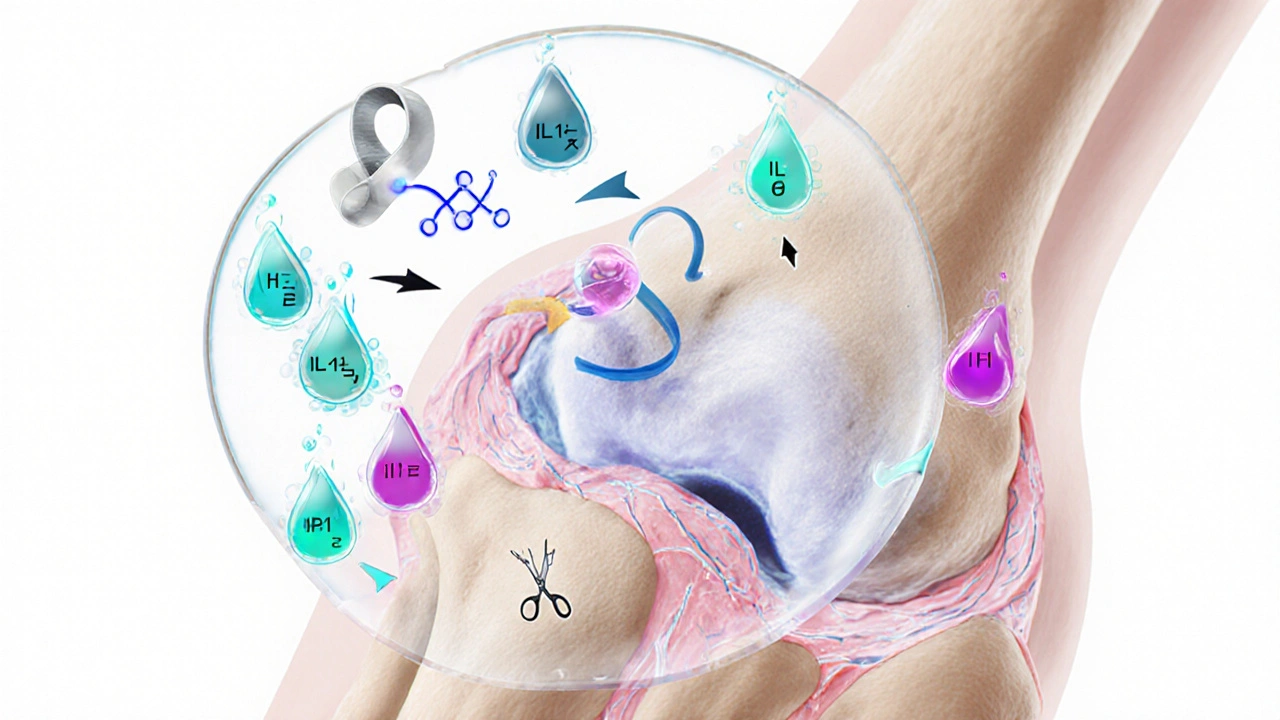

Cytokines: The Chemical Messengers Driving Damage

Cytokine is a small protein released by immune cells that regulates inflammation and cell communication. In osteoarthritis, several cytokines act like gasoline on a fire.

| cytokine | main source | effect on joint |

|---|---|---|

| IL‑1β | Synovial macrophages | Stimulates matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) → cartilage breakdown |

| TNF‑α | Activated T‑cells, macrophages | Promotes osteoclast activity → subchondral bone erosion |

| IL‑6 | Fibroblast‑like synoviocytes | Drives systemic acute‑phase response, pain sensitization |

| IFN‑γ | Th1 cells | Amplifies macrophage activation, perpetuates inflammation |

Targeting these cytokines-either directly with biologics or indirectly via small molecules-has become a hot research area.

Biomarkers: Spotting Autoimmune Activity Early

Biomarker is a measurable indicator of a biological state or condition. In osteoarthritis, biomarkers help differentiate “pure wear‑and‑tear” from immune‑driven disease.

- Anti‑CCP antibodies: Traditionally a rheumatoid arthritis marker, low‑titer positivity has been observed in ~12% of osteoarthritis patients with high synovitis scores.

- Serum MMP‑13: Elevated levels correlate with cartilage loss and increased IL‑1β activity.

- Synovial fluid IL‑6/IL‑1β ratio: A ratio >2 predicts rapid radiographic progression.

When physicians detect these signals, they may consider an immune‑modulating treatment plan rather than just painkillers.

Therapeutic Shift: From Analgesics to Immune Modulators

Historically, osteoarthritis care focused on NSAIDs, physical therapy, and joint replacement. The autoimmune angle is changing that playbook.

- Low‑dose methotrexate: Small trials in 2024 showed modest pain reduction and slowed cartilage loss in patients with elevated CRP.

- IL‑1β inhibitors (e.g., canakinumab): A 2025 phaseII study reported a 30% drop in synovial inflammation markers, though the effect on structural progression remains under review.

- JAK inhibitors: By dampening cytokine signaling, drugs like tofacitinib are being repurposed for osteoarthritis with promising early‑phase data.

These agents are often grouped under the umbrella of disease‑modifying osteoarthritis drug (DMOAD). While the term is still evolving, the goal is clear: halt or reverse joint damage rather than merely mask symptoms.

Practical Steps for Patients and Clinicians

- Assess risk: Look for family history of autoimmune disease, early‑onset joint pain, and high‑impact occupations.

- Order baseline labs: CRP, ESR, anti‑CCP, and a cytokine panel if available.

- Imaging: MRI can reveal synovial thickening and bone marrow lesions that suggest inflammation.

- Customize therapy: If biomarkers indicate an immune component, discuss low‑dose immunomodulators alongside standard NSAIDs and rehab.

- Monitor: Re‑evaluate pain scores, functional questionnaires, and biomarker levels every 3-6months.

By following this roadmap, clinicians can catch the autoimmune surge early and intervene before irreversible cartilage loss occurs.

Future Directions: What’s on the Horizon?

Research is racing ahead on three fronts:

- Precision medicine: Genotype‑guided therapy (e.g., HLA‑DRB1 typing) could predict who benefits most from immunomodulators.

- Novel targets: Small‑molecule inhibitors of the NLRP3 inflammasome are in phaseI trials, aiming to block IL‑1β activation at its source.

- Regenerative combos: Combining stem‑cell injections with cytokine blockers may promote cartilage repair while keeping inflammation in check.

As the evidence base expands, the line between “wear‑and‑tear” and “autoimmune” osteoarthritis will blur, ushering in a new era of personalized joint care.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is osteoarthritis really an autoimmune disease?

Osteoarthritis is primarily a degenerative joint disease, but many patients show immune‑driven inflammation. When biomarkers, genetic markers, or imaging reveal an autoimmune component, doctors may treat it as such.

Can standard NSAIDs control the immune aspect?

NSAIDs reduce pain and some inflammation, but they don’t target the cytokine pathways that drive autoimmunity. For patients with high inflammatory markers, additional immune‑modulating drugs are often needed.

What lifestyle changes help if autoimmunity is involved?

Weight management, low‑impact exercise (e.g., swimming), and an anti‑inflammatory diet rich in omega‑3s can lower systemic inflammation, complementing medication.

Are there risks with using drugs like methotrexate for osteoarthritis?

Low‑dose methotrexate is generally safe, but it can affect liver function and blood counts. Regular labs every 8-12weeks are recommended.

How soon can I expect pain relief from immune‑targeted therapies?

Patients often report noticeable pain reduction within 4-6weeks, though structural benefits (slowing cartilage loss) may take 6-12months to demonstrate on imaging.

Comments

virginia sancho

October 3, 2025 AT 18:43Wow, the link between autoimmunity and osteoarthritis is eye‑opening.

Namit Kumar

October 4, 2025 AT 20:57Totally mind‑blowing stuff 😲 The immune system really does more than just fight germs, it can turn our joints into battlegrounds.

Sam Rail

October 5, 2025 AT 23:11Looks like another fancy spin on old arthritis stuff, but yeah, some people do have more inflammation.

Lisa Lower

October 7, 2025 AT 01:26Let me break this down for folks who want the full picture It starts with the fact that cartilage breakdown is not just a mechanical wear problem The immune system can sense cartilage fragments and treat them like foreign invaders which leads to chronic inflammation Over time those immune cells release cytokines like IL‑1β and TNF‑α that accelerate matrix metalloproteinase activity and further degrade the joint matrix At the same time certain genetic markers such as HLA‑DRB1*04:01 make the immune system more likely to present cartilage peptides to T‑cells turning a normal repair response into an auto‑reactive attack On top of that elevated CRP or anti‑CCP antibodies are practical biomarkers that clinicians can use to flag the immune component in a patient who otherwise looks like a typical wear‑and‑tear case Lifestyle factors such as a high‑impact job or obesity add more mechanical stress which fuels the inflammatory loop The new wave of treatments is all about targeting those cytokine pathways low‑dose methotrexate has shown some promise and JAK inhibitors are being repurposed to curb the signaling cascade Meanwhile researchers are testing NLRP3 inflammasome blockers that could stop IL‑1β activation at the source In practice this means a patient with early‑onset knee pain and a family history of autoimmunity might get a blood panel, a MRI looking for synovial thickening and, if the markers line up, a trial of an immune‑modulating drug instead of just NSAIDs The goal is to halt the vicious cycle before cartilage is lost irreversibly This approach is still evolving but the data from 2023‑2025 suggest we are moving toward a more personalized, precision‑medicine model for osteoarthritis

Dana Sellers

October 8, 2025 AT 03:40Yeah that sounds cool but keep it simple for the rest of us basic stuff helps.

Damon Farnham

October 9, 2025 AT 05:55One must, however, be exceedingly cautious when embracing novel immunomodulatory therapies; the long‑term safety profile remains, at best, incompletely characterized. Excessive reliance on off‑label use could precipitate unforeseen adverse events! Moreover, the economic burden on healthcare systems cannot be ignored; biologics and JAK inhibitors are prohibitively expensive for many patients. Regulatory bodies demand robust phase‑III data, yet many trials are still in phase‑II, leaving a gap between hopeful headlines and actionable guidelines. Practitioners should therefore weigh risks versus benefits meticulously, perhaps reserving such interventions for cases with clear biomarker elevation and documented disease progression despite conventional therapy.

Marsha Saminathan

October 10, 2025 AT 08:09Yo this is like a sci‑fi plot but with real labs and knees it's wild the whole thing about gene tags and cytokine storms and the way doctors could mix stem cells with blockers is kinda next‑level magic it's not just pills and PT anymore the future sounds colorful and hopeful

Justin Park

October 11, 2025 AT 10:23🤔 The philosophical angle here is fascinating – we’re blurring the line between what we consider “degenerative” and “immune‑mediated.” If the body’s own defenses can turn a joint into a battlefield, then isn’t the disease a miscommunication rather than a pure wear‑and‑tear event? This raises questions about identity of the disease, treatment ethics, and how we define “normal” aging.

Herman Rochelle

October 12, 2025 AT 12:38Good point. It’s helpful to think of the immune system as a double‑edged sword. When we catch the inflammatory signals early, we can intervene before irreversible damage sets in.

ADETUNJI ADEPOJU

October 13, 2025 AT 14:52Ah, the classic “new hype” narrative masquerading as breakthrough. Yet the data are riddled with confounding variables, and the jargon-heavy sections read like a corporate whitepaper. One must remain skeptical of sweeping claims that a handful of biomarkers can fully predict a complex, multifactorial disease.

David McClone

October 14, 2025 AT 17:07Right, because nothing says “trust me” like an over‑dramatic slide deck full of buzzwords. Still, kudos for throwing a few real‑world trial numbers into the mix-even if they’re as scattered as a tossed salad.

Jessica Romero

October 15, 2025 AT 19:21From a collaborative standpoint, integrating genetic screening with longitudinal biomarker tracking could revolutionize patient stratification. By employing a multi‑modal approach-combining MRI‑based synovial thickness metrics, serum cytokine panels, and HLA‑DRB1 typing-clinicians can construct a nuanced risk profile. This paradigm shift not only personalizes therapeutic regimens but also aligns with the broader movement toward precision medicine in rheumatology. Moreover, the inclusion of lifestyle modifiers such as diet, exercise, and occupational ergonomics further refines the management plan, ensuring that interventions are both targeted and holistic. Ultimately, this comprehensive framework promises to improve outcomes while reducing unnecessary exposure to broad‑spectrum anti‑inflammatory drugs.

Michele Radford

October 16, 2025 AT 21:35The article tries to sound groundbreaking but it’s just rehashing old concepts with a shiny veneer. The claim that a handful of cytokine blockers will “halt” cartilage loss is overly optimistic; clinical endpoints still lag behind expectations.

Suzanne Podany

October 17, 2025 AT 23:50Let’s keep the conversation inclusive and remember that access to these advanced diagnostics isn’t universal. We should advocate for broader insurance coverage and community outreach so that all patients benefit from emerging research.

Nina Vera

October 19, 2025 AT 02:04OMG this is the drama we’ve been waiting for!!! Finally, science meets the spotlight and we get to see real change in joint care!!!